DRUM’s Soulful Beat:

DESIS Embodying Radical Healing

By Sheena Sood

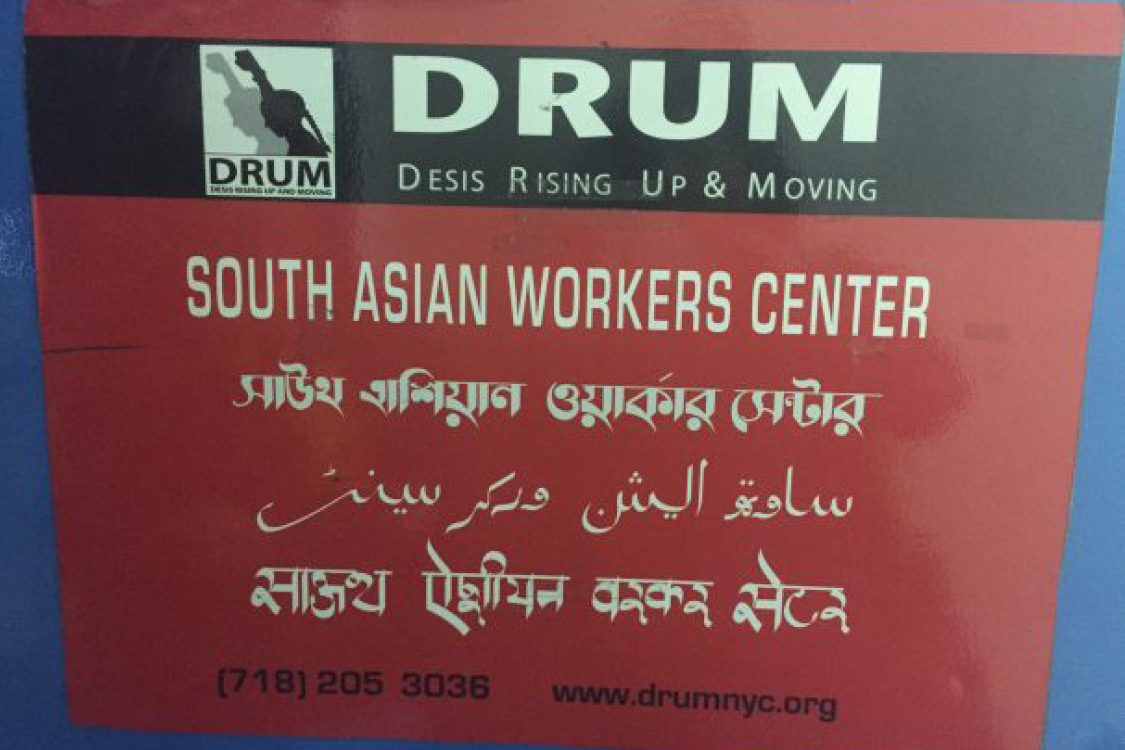

Last winter, I had the privilege of learning more about the organization Desis Rising Up and Moving (DRUM) through gathering data for my dissertation study. Before beginning the project, I understood little beyond DRUM’s mission. I knew DRUM as “a multigenerational, membership-led organization of low-wage South Asian immigrant workers and youth based in New York City” (DRUM 2014). I respected their intention to build political power and leadership amongst working class immigrants in the South Asian community: I wanted to learn more about DRUM’s approach to organizing campaigns in Jackson Heights, Queens. The intent of my dissertation was to explore how South Asian organizations develop political agendas and build alliances beyond their ethnic communities. As the data collection process concluded, I felt overwhelmed by the rich data but still determined to tackle the analysis stage; however, I also walked away transformed by the work I witnessed DRUM was doing beneath, above and beyond the “political” sphere – namely in domain of healing justice.

Every interview forced me to witness the transformative community impact that was taking place through DRUM’s work, moving members from a place of shared trauma to one of collective healing. I often left their space motivated to cultivate a more critical approach to engaging in radical healing practices that center those most marginalized in movements and communities. I explore that conversation in this article. I contribute to Grace Lee Boggs’ beliefs on “transformational organizing” and Ginwright’s, framework of “radical healing” to shine light on DRUM’s approach to political organizing as an embodiment of “healing justice” and community transformation in an era of collective, cross-generational trauma (Boggs, Kurashige, and Glover 2012; Ginwright 2009, 2015). I write this essay not to glorify the struggles of working class communities on the front lines of oppression and resistance, but to lift up the community care approaches they already embody.

From Isolation to Belonging

I recall a meeting with one of the youth members Manny Yusuf at the DRUM office in Jackson Heights, Queens. It was a particularly frigid Saturday morning. She began the conversation by sharing that she was 14-years old when her mom enrolled her in DRUM’s YouthPower! program. Prior to that, Manny’s mom and her were unsure how to process their status as undocumented immigrants: “Before this, we were on my dad’s H-1 visa, [so] my mom was having a really hard time being undocumented. She wanted a space where she could talk to people, other undocumented people” (personal communication, February 27, 2016).

Manny’s mom was introduced to DRUM through the recommendation of a neighbor who was also undocumented. After attending her first DRUM meeting in 2010, Manny’s mom enrolled Manny in the summer program. At first, Manny didn’t want to enroll. She chuckled as she recalled her initial trepidation, “then I did the internship and six years later, here I am” (personal communication, February 27, 2016). When I asked what encouraged her to stay involved in DRUM after the summer program, Manny stated, “I didn’t know what it meant to be undocumented…. My mom told me we’re undocumented [and] we don’t have papers, but I didn’t realize what that meant, nor did I care” (personal communication, February 27, 2016). At DRUM, Manny met other working class South Asians who shared her status and struggles. Manny learned about DRUM’s history of helping members organize campaigns to fight for justice. Through attending youth and coalition meetings, Manny recalls, “I began to understand… you are never too young to start organizing” (personal communication, February 27, 2016).

We were only minutes into our conversation when Manny alluded to the personal transformation she experienced through her involvement: “Because of DRUM, I wouldn’t be as corny as to say I found myself, but it’s true. I became very open and super loud, very social. I think it really made me the person I wanted to be but couldn’t be because I was afraid” (personal communication, February 27, 2016). Throughout the interview, Manny mentioned how DRUM helped her learn how to operate from a space of courage rather than fear, see her struggle as interconnected with other people of color instead of individualized, develop human relationships across political struggles, and, unapologetically, own her queer, working class, undocumented, immigrant, South Asian identity. She stressed, “DRUM is a multigenerational organization that works on a lot of different issues, like educational justice, racial justice, immigrant justice, and workers’ rights issues. That’s like the definition I give, but it’s so much more than that because you know DRUM has like helped politicize so many people and not only that, it’s just like, like a community space, and everybody here is like exactly like family” (personal communication, February 27, 2016).

The deeper I dove into understanding their stories and DRUM’s values, the more I realized Manny was not alone in her experiences. DRUM’s director of organizing, Kazi Fouzia also shared her first experiences working with the organization. On a winter day in 2010, a taxi driver accidentally struck Kazi. After the accident, she faced repeated battles with regard to her physical and emotional health – largely because she had little understanding of her rights as an undocumented immigrant and was afraid to report the incident to a police precinct. Thus, Kazi never received proper attention and medical care at the hospital. Upon returning to her job as a seamstress, Kazi’s employer fired her because her sustained injuries slowed down her productivity: “The guy fired me right away because my hand was not working at that time. I felt so isolated. Then I came back to DRUM. I discussed [my situation] with the members and leaders…and with labor department people and labor rights activists…. I decided to file a lawsuit against the shops owners, and I won! I realized undocumented immigrants have rights to fight for their justice” (personal communication, February 27, 2016).

All of the conversations wove a common thread of the influence structural oppression has on their lives. The interviews carried a heavy weight, forcing me to stomach the depth of collective trauma working class immigrant families, also vulnerable to systemic Islamophobia and racial profiling, experience. The continuation of systemic oppression, implementation of neoliberal government policies, privatized investment in mass incarceration, and long-term disinvestment in urban communities of color produce the conditions for structural violence to perpetuate. This violence includes but is not limited to exploitation of low-wage workers, under-resourced schools and state-sanctioned violence in the form of police brutality, racial profiling, zero tolerance policies, increased deportations, and mass surveillance.

Prior to joining DRUM, there was a common narrative of members feeling alienated, hopeless and fearful about overcoming personal struggles and facing obstacles in maintaining their overall health and well-being. Given the material struggles and series of emotional, mental and spiritual wounds DRUM members face on a daily basis, their sense of helplessness in being able to alter their social environment and imagine a life free from oppression was not uncommon. However, their common experience of structural violence is also what allowed them to connect each other’s pain to a sense of collective trauma. In listening to their stories, I was constantly reminded of how the intention of “healing” is to move individuals from a sense of brokenness, trauma, and distrust into one of wholeness, relief and trustful, imaginative hope.

When individuals whose lives are deeply impacted by oppression feel so disconnected from naming their oppression that they are unable to connect their struggles to a structural analysis, they are unable to transform this collective trauma.

Participants remarked on how instead of blaming members for their problems and pushing them to adopt different behaviors as a remedy, DRUM works with members to help them analyze their struggles through a political lens and pushes them to understand how to advocate for their rights. The organization’s objective to organize their membership toward collective action focuses on instilling leadership and organizing skills in each member to achieve such political and social change. Each of my interviews illustrates that, in DRUM, members found a family that understood them and renewed their sense of hope and purpose, both in analyzing and connecting their personal struggles and in building campaigns to advocate for their own rights. Although Manny, Kazi and the other members barely uttered the words “healing” when discussing DRUM’s mission or their experience working with the organization, their reflections left me considering how, in helping restore a sense of faith in its members and empowering them to be agents of change around their interconnected struggles, DRUM’s political work is a default process of healing.

Making the Leap: From Individualized to Collective Notions of Mindfulness and Healing

In an essay entitled “These Are the Times to Grow Our Souls,” long-time revolutionary organizer Grace Lee Boggs emphasized a need for human beings to speed up our spiritual evolution and our practice of love and compassion for self and others. Her reasoning was rooted in a recognition of how dehumanized we have become through living in a capitalist, hyper-individualist, hyper-materialist society and of how more and more of our working class adults and youth are seen and see themselves as expendable (Boggs 1998:146; Boggs et al. 2012) Boggs encouraged aspiring revolutionaries to consider how:

These are the times that try our souls. Each of us needs to undergo a tremendous philosophical and spiritual transformation…to be awakened to a personal and compassionate recognition of the inseparable interconnection between our minds, hearts, and bodies; between our physical and psychical well-being; and between ourselves and all the other selves in our country and in the world” (Boggs et al. 2012:34).

Her insistence that revolutionaries invest in the struggle to transform themselves is a crucial and integral element to her philosophy of social change:

“To make a revolution, people must not only struggle against existing institutions. They must make a philosophical/spiritual leap and become more human human beings. In order to change/transform the world, they must change/transform themselves” (Boggs 1998:153).

Boggs’ emphasis on the internal and external elements of transformational organizing builds on the writings and practices of Black queer feminist revolutionaries and writers who were some of the first to exemplify transformational organizing and collective healing in our movements. Boggs’s philosophical approach aligns with the dialogue organizers and activists, today, are having about the need for mindfulness and healing in our movements. Mindfulness, as an intentional practice, invites conscious awareness to the present moment and to one’s emotions, feelings and surroundings. Mindfulness can have a transformative and often positive impact on our sense of self and how we interact with others and the world. As someone who has experienced transformative growth in my awareness to self and the present moment through my own sustained practice of mindfulness, I appreciate how the dialogue on mindfulness, spiritual health and well-being has mushroomed in organizing communities.

Sadly, mainstream understandings of healing and mindfulness are made obsolete and inaccessible to many. Furthermore, when had, these conversations often place an emphasis on individual self-care and exclude a holistic analysis of how communities can work toward collective healing and well-being. I believe part of the reason why mainstream conversations emphasize individual healing without taking into consideration the significance of collective wellness is because the logic of capitalism assumes we must put our individual needs and desires ahead of those in our communities.

As a result, we are encouraged to conceptualize trauma through individualized, not collective, frameworks. Although people have individual, unique experiences with trauma, trauma is also experienced collectively. Unfortunately, existing research seldom speaks on the experience of trauma as collective, and most frameworks fail to understand the root causes of trauma as connected to the persistence of social and political oppression. These frameworks do not consider how community organizations play a crucial role in transforming collective trauma. The issue with an individualized framing of mindfulness is that it does not allow humans to pinpoint the origin of what causes our sense of hopelessness, so that we can transform our collective trauma and change the conditions that harm our well-being.

Not only do we individualize the causation of trauma, but as a society, we also tend to offer an individualized approach to healing. The focus is on you, your healing, your yoga practice, your process, your space, your breaks, your days off, your transformation, you, you, and more you. Rarely is it about us, we, or collective transformation. This framework concerns me. It is not that healing at the individual level is not important. The need for mindfulness in an age of constant distraction cannot simply be about the need for us to individually disconnect from social media and our workplaces to find peace and balance within ourselves. It has also got to be about how we challenge the logic of capitalism by constructing collective spaces for mindfulness and repairing our human relationships with one another through face-to-face connections.

If we intend to transform the world and the oppressive structures of society while also shifting our shared trauma into a sense of collective well-being, then the dialogue and practice of healing must happen in community and in human connection with one another.

There is a growing need for healing and mindfulness at the collective level – notably for those who experience oppression in the deepest and most intersecting ways – and for transformation to a framework that recognizes the significance of collective well-being.

Given that our society can barely acknowledge, let alone, come to terms with ongoing political oppression in our social environments as a form of trauma, how do we conceptualize what healing looks like in communities most impacted by intersecting oppressions (e.g. raced, classed, gendered, embodied, etc.)? How do communities ravaged by an experience of loss and violence practice wellness when surrounded by environmental and political chaos? Is mindfulness and collective healing amidst the persistence of such ongoing trauma even possible for those who do not have the luxury of ignoring systemic oppression in their daily struggles?

DRUM’s framework is one that embodies collective healing. Communities on the front lines of resisting political and social oppression are promoting practices that encourage the well-being and healing of their collective whole. For as long as Indigenous and Black communities have faced oppression in the United States, they have engaged in practices of wellness and healing at the collective level – through sacred rituals with mother earth and the existence of the Black church, artistic creation and expression such as Black spirituals, the blues and jazz, and training families how to defend their communities from settlers, slave owners and other oppressors. Those most affected by intersecting oppression must continue to be the ones articulating what healing and well-being looks like for them.

Radical Healing: A Framework for Politicizing Healing, Transformation and Mindfulness

Shawn Ginwright introduces the framework of “healing justice” and the process of “radical healing” in his studies of a youth leadership organization in Oakland, California in which he is actively involved (2009, 2015). He argues,

Healing from the trauma of oppression caused by poverty, racism, sexism, homophobia, and class exploitation is an important political act. Without a critical understanding of how the various structures of domination operate in our daily lives we cannot begin to develop meaningful forms of personal and collective resistance. Healing occurs when we reconcile painful experiences resulting from oppression through testimony and naming what may seem to be personal misfortune as systemic oppression (2009:9).

Primarily, Ginwright’s emphasis on naming the root cause of oppression as a process of healing itself is crucial. Secondly, “rather than viewing well-being as an individual act of self-care,” Ginwright suggests “healing justice advocates view healing as political action. Healing is political because those that focus on healing in urban communities recognize how structural oppression threatens the well-being of individuals and communities” (2015:8).

Healing justice advocates and practitioners understand “well-being as a collective necessity, rather than individual choice… [and see how] community organizing and acting in ways that improve communities builds a sense of control, agency, and self-determination (2015:8). Ginwright considers four areas of Black life that contribute to the radical healing process:

1. Caring relationships that connect Black people to a history of resistance, struggle and triumph;

2. Community as a space that offers members an opportunity to restore hope and love through acknowledging shared struggles and fears;

3. Critical consciousness through emphasizing the intersection of personal struggles and political explanations; and

4. Culture through helping folks develop a healthy relationship to their racial and ethnic identity and providing them the support and means to contribute to evolving their identity (2009:9–10).

Ginwright’s research is valuable because he conceptualizes oppression as a form of social and collective trauma. This conceptualization of oppression allows him to name trauma as a condition that is rooted in something deeper than the individual. Such recognition provides space for Ginwright to discuss the need for a collective process of restoration and healing in order to bring communities to a space of collective well-being. Furthermore, his framework pushes us to view community organizations – particularly those that center working class leadership – as pioneers in contributing to the political act of healing. Community organizations engage in “radical healing” when they: 1) Cultivate members’ ability to name the root causes of violence, injustice, and pain affecting their lives and; 2) Hold space for their members’ self-transformation as organizers.

In writing this piece, I contribute to Ginwright’s framework by naming DRUM’s efforts as “healing justice” work. DRUM’s efforts to change ordinary people’s political, economic and social conditions via collective well-being is not valued as healing because of the priority and focus placed on capitalistic notions of individual healing and self-care. It is important to identify DRUM’s work as a process of “radical healing” because it encourages our societies to work toward collective well-being.

DRUM’s Embodiment of “Radical Healing”

Although Ginwright’s study focuses primarily on Black youth in urban communities, his concepts of “healing justice” and “radical healing” are applicable to DRUM’s work. The issues and struggles the working class South Asian American (SAA) community in Jackson Heights face are not the same as Black youth in urban communities; however, they are relatable (oftentimes more relatable than those faced by middle- and upper-middle class SAA). The low-income immigrant families in Jackson Heights experience trauma and pain in similar ways to the low-income Black and Latino families in nearby neighborhoods (e.g. through common fears of being deported or incarcerated), and the root cause of their trauma is connected to similar systems of oppression. Although Ginwright’s consideration of how four areas of Black life that contribute to their radical healing process is applicable to DRUM, the ways DRUM embodies these areas is unique to the issues, social environment and cultural history of its working class SAA members. For the purpose of this piece, I focus on DRUM’s expression of caring relationships, community and critical consciousness to discuss how DRUM engages in a process of “radical healing.” These areas of radical healing are illustrated through the experiences Manny and Kazi shared about their entry to DRUM and also through the caring cross-generational relationships developed in DRUM’s space.

Healing is a process that allows us to move from trauma to wellness, from fear to courage, from hopelessness to confidence and optimism

The relationships cultivated in DRUM’s space have a profound impact on how members relate to and draw connections between their struggles. DRUM’s focus on intergenerational organizing values adult-youth relationships in a non-hierarchical way, connecting each membership group across campaigns. Multiple youth members shared how comfortable they feel in approaching adult members about their personal life struggles or about how they are questioning their gender, sexuality or relationships – practices they identify as generally rare in South Asian culture. DRUM’s intention toward dismantling hierarchical norms on an internal level is refreshing and significant, for it prepares members to engage in inter-generational organizing and resistance struggles together. DRUM is strategic in how it pushes youth and adult members to draw connections between their respective campaigns. Roksana Mun, current Director of Strategy and Trainings, emphasized the detrimental effect it has on our campaigns and movements when immigrant youth focus their efforts solely on passing legislation such as the DREAM act and Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) without understanding the impact these policies may have on adult members of their community – often their parents (personal communication, March 3rd, 2016).

A similar disconnection in political struggles occurs when adult members fail to see the parallels between the harassment they experience from law enforcement as street vendors and the harassment youth experience due to zero tolerance policies and the school-to-prison pipeline. DRUM’s effort to draw connections between these issues does not simply happen in the streets or advocacy campaigns. It also happens through the organization’s practice of having adults and youth attend each other’s membership meetings. It happens when adult members participate in a youth-led Eckshate Liberation Dhaba for Gender Justice in Diversity Plaza, an open and inter-generational public space and ethnic enclave of Jackson Heights businesses. According to Mun, it is in these relationship-building moments that the “osmosis of experience being transferred” occurs across generations (personal communication, March 3rd, 2016).

In November 2015, I attended DRUM’s Mela, a fundraiser and celebration of its 15th year of organizing. I noticed immediately how the space burst with collective joy. I could sense how connected members felt to one another. Whether they were sharing about the ongoing struggles of formerly detained refugees who recently came off their hunger strike campaign or performing choreographed dances together, I noticed how strong and familial, loving and humanizing their bonds felt. In August 2016, I noticed a similar sense of fulfilment and purpose while participating in their Eckshate gender justice Liberation Dhaba and attending their Youth Power! graduation ceremony. Their shared dedication to teaching strangers in their community about gender policing and discussing what they learned about the dangers of the “Countering Violent Extremism” program was inspiring. Not only did it feel like a place where youth and adults felt a sense of belonging, but ninety percent of the leaders I spoke with told me some variation of “DRUM feels like a family.” Mahira described the level of economic depravity and isolation from South Asian communities that her mom, her sister and her experienced after her mom and dad divorced (personal communication February 26, 2016). DRUM worked to counter her and her sister Jensine’s sense of alienation and distrust with the South Asian community by introducing them to a community they “had never been a part of [,]” where “people were like so cool and… shared the same experiences” (personal communication February 26, 2016). Belonging occurs when individuals feel they are a part of something greater than themselves. I believe radical healing occurs at DRUM when members feel a sense of belonging to community and an investment in that community’s collective liberation.

DRUM’s investment in cultivating radical consciousness of their members also contributes to the radical healing process by connecting them to a rich cross-racial struggle for justice and human rights. DRUM’s focus on reframing the narrative typically presented to SAA about their immigrant and cultural history through political education is a crucial segment of their work. Instead of perpetuating the “model minority myth” by encouraging their members to believe their individual behaviors are responsible for their personal struggles, DRUM pushes members to understand that there are political explanations for the obstacles they experience as low-wage workers, undocumented immigrants, surveilled and structurally under-resourced communities. As opposed to lifting up the narratives of SAA who assimilated into corporate America or highly-skilled occupations, Mun discussed how DRUM shares the often invisibilized histories of SAA, including Punjabi farmers who married Mexican immigrants in the early Twentieth century, Bengali merchants who married into African American, Dominican and Puerto Rican families, and Sikh day laborers who worked alongside Chinese laborers to build railroads in the late 1800s (personal communication, March 3rd, 2016). DRUM’s emphasis on pushing members to develop their own consciousness through these broader political frameworks is done with an intention to shine light on the full history of South Asian Americans, not simply the narratives of those seeking incorporation into what Mun identifies as “white assimilationist middle class” structures (personal communication, March 3rd, 2016).

Mun explains that by complicating the narrative, South Asians can recognize “there’s a real affinity and history there to ground into, to actually align ourselves automatically to the Black and Latino communities of this country,” in a familial and cultural sense (personal communication, March 3rd, 2016). This translates into what board member Kazembe Balagun identifies as authentic cross-racial solidarity when he shared, “The important thing about DRUM is that before there was a hashtag, a sweater, a fitted sweatband or whatever, Black lives mattered at DRUM, and the thing about the acculturation process in the United States around immigrant experiences is a race question, like how are you going to identify in terms of like your race?” (personal communication, February 5th, 2016). DRUM’s emphasis on critical consciousness and authentic cross-racial solidarity allows working class SAA communities to see their own narratives, immigrant histories and multiracial solidarity movements lifted up and as significant. This results in their ability to participate as agents in a longer history of political struggles and to feel a greater sense of belonging – to their identity as working-class, as South Asian, as people of color in communities connected to profound traditions of resistance.

Critical consciousness also means that DRUM supports working class Muslim communities who are subject to mass surveillance and racial profiling and whose family members have been detained or arrested for suspicion and fabricated terrorist charges in an era of systemic Islamophobia. DRUM recognizes how the government uses Muslim families as scapegoats to make the public believe they are taking action in defense of national security. For instance, long-time DRUM leader Shahina recounted DRUM’s support for her son Siraj following his entrapment into a manufactured terrorist case (personal communication, August 7th, 2016). Post 9/11, New York Police Department (NYPD) informants were paid to surveil Muslim communities. Working class communities in urban areas were the most systemically affected by these “national security” strategies. At a time when most mainstream SAA organizations were unwilling to draw attention to the connections between mass surveillance, state-sanctioned violence and national security and how it resulted in the manufacturing of terrorism charges and the widespread detention of innocent Muslim families, DRUM organized hotlines and developed racial and immigrant justice campaigns that demonstrated how the struggle Shahina’s family faced was connected to a long-time tradition of Islamophobia and imperialist policies utilized by the United States government to justify military occupation abroad, particularly in the Middle East and South Asia.

When I spoke with Shahina, she shared the structural violence and trauma that she and her family have suffered following her son’s arrest in 2004 (personal communication, August 14th, 2016). Her home has been raided; she and her family have been detained. Her husband was placed on house arrest and required to wear an electronic monitor. Despite these traumas, one of the most remarkable takeaways I felt from listening to her story and talking to Siraj on the phone was their genuine appreciation for DRUM.

One hot summer day, I drove her and her family to visit Siraj in prison. On the drive there and back, Shahina shared how, despite the continued state of emotional and physical suffering and depression her family endures, the support she received from DRUM made her feel a sense of hope and empowerment (personal communication, August 13th, 2016). At DRUM, she did not feel a need to apologize for her religious practice of her understanding that her son was unjustly entrapped on false accounts of terrorism. Even when her extended family and relatives rejected her efforts to advocate on her son’s behalf, DRUM stepped in and helped the members and greater community develop a political analysis of how Siraj’s case is tied to systemic Islamophobia and fear-based national security policies. Today, Shahina remains one of lead adult organizers in the membership and is respected throughout DRUM’s community. All of this is radical healing.

As before mentioned, healing is a process that allows us to move from trauma to wellness, from fear to courage, from hopelessness to confidence and optimism. Although many mainstream interpretations of healing would have one believe healing is an individualized process or a transformation of the individual body, mind and spirit (i.e. when I believe I’m better, I can heal myself;), such emphasis on individual positivity is quite limiting and problematic. Healing is about restoration on an internal and spiritual level, but healing is also about empowering those who are most oppressed to believe in their capacity to transform the social, political and even material conditions that have a tangible and direct effect their well-being.

When individuals come together to connect social struggles and build campaigns to eradicate the oppressive conditions that cause those struggles, they are, according to Ginwright, engaging in “radical healing.” In this way, healing is both an internal and an external process. Healing takes place when human beings recognize their inter-connectivity to one another and, thereby, work to improve the social, political and material conditions that affect not simply themselves but also the conditions that affect the rest of humanity. By focusing on attaining community wellness through addressing the root causes of oppression instead of focusing on individualized notions of wellness, they are engaging in a process of collective healing. This maxim is evident in the words Kazembe shared on his evaluation of DRUM’s work:

Part of who I am as a person… seeks to kind of draw from that…, in a very deeply African American way of what Henry Louis Gates would call signifying you know like you bring your own particular meaning to the politic… so like I’ve been experimenting with this term called ‘socialism,’ like S-O-U-L, so “Soul-cialism” because it speaks specifically to words, to a place that we need to go. It also speaks directly to those non-commodified parts of our soul and… our body, the soul that all of our communities have… that we have to really lift up, in this moment, you know in particular in a moment when so many of our communities are under attack… I don’t think enough people talk about the soul like S-O-U-L as a political force but soul matters, and that’s another thing I like about DRUM. They got soul, [and] …soul actually is around aspiration and overcoming, and it confronts individual pleasure with collective joy as Cornel West would say. Soul looks at that role of collective joy in our political work part, [and] when I say joy, I’m not saying having to be happy all the time, but I’m talking about like the actual connection of human beings in a process is important, and again, DRUM has that (personal communication, February 5th, 2016).

Conclusion

DRUM’s work helps transform members’ sense of isolation into one of belonging, confusion into analysis, hopelessness into hope, disempowerment into empowerment, and helplessness into strategic action. Their work is not limited to the political sphere, so neither can my understanding and analysis. DRUM helps transform their members’ sense of victimization into agency and restores their communities’ faith and hope in themselves. They exemplify what what Yashna Padamsee identifies as “communities of care” when she encourages “communities to create structures in which self-care changes to community care” (2011). Though the changes for which DRUM members advocate focus on the external social environment, the community care work is holistic and deeply transformative – internally and externally. Though members did not use the word “healing,” all of me was deeply aware that what I was hearing them discuss in our interviews was an experience of “radical healing.”

This essay discusses DRUM as a model for radical healing. I share this perspective because I sincerely believe that DRUM provides a space where members come together and feel the essence of healing through their connection to people who know their struggle and are also willing to fight with and struggle for justice with them. At the same time, this does not mean that DRUM members and staff do not experience depletion of their energy and resources. It also does not mean that, by stepping into DRUM’s space, their collective trauma is magically transformed into a sense of collective joy. Staff leaders and member leaders face ongoing economic, social and political struggles. The capitalist culture of social justice organizing is hierarchical: the groups who are most impacted by oppression are the ones, on the front lines, sacrificing their health and well-being in their struggle for justice. In addition to experiencing fatigue and harm to their well-being, they constantly struggle to sustain their programs. I believe this is largely because as a whole, society does not value the type of political engagement that empowers individuals to organize and liberate themselves toward freedom. This needs to change. A portion of that change must happen through divesting from the notion that revolution will happen through social media. We must recognize our collective responsibility to be more engaged in freedom struggles on our blocks and in our streets – in real-time relationships that help community members identify common struggles and fight for solutions together.

Honestly, I do not know of a more influential way that individuals can practice “mindfulness” and affect social change than through involving themselves in or investing in an organization dedicated to grassroots community-organizing. Community-organizing reconnects us to our own sense of humanity by engaging us in an act of mindfulness that prioritizes the collective whole. Transformational community-organizing reorients how we advocate for changes in our society by encouraging us to evolve in our relationships with ourselves, our friends and families, and with our movements. Transformational community-organizing with a “healing justice” lens – as exemplified by DRUM’s model for political organizing – radically heals and transmutes our collective trauma into a sense of holistic liberation (Ginwright 2015). We can all learn more than a thing or two about radical healing from DRUM’s approach to transformative political organizing. Donate to support DRUM’s amazing work by clicking here now!

I am grateful to the amazing DRUM family members for their time and stories, to my Philly community for an overflow of constant rejuvenation and radical love, and to my friends and chosen family who graced me with their eyes, ears, heart, touch, soul and words – in particular Alexis Pauline Gumbs, Nehad Khader, Mari Morales-Williams, Jardana Peacock, Willie Jamal Right – as I grew with this piece these past few months and to the philosophers theorists, healing justice practitioners and organizers who inspired my understanding of the themes I weave through in this article that hopefully brings us all closer to a space of “radical healing.”

References:

Boggs, Grace Lee. 1998. Living For Change: An Autobiography. 2nd ed. edition. Minneapolis: Univ Of Minnesota Press.

Boggs, Grace Lee, Scott Kurashige, and Danny Glover. 2012. The Next American Revolution: Sustainable Activism for the Twenty-First Century. First Edition, Updated and Expanded Edition, New Afterword with Immanuel Wallers edition. Berkeley: University of California Press.

DRUM. 2014. “South Asian Organizing Center.” Retrieved (http://www.drumnyc.org/).

Ginwright, Shawn. 2015. Hope and Healing in Urban Education: How Urban Activists and Teachers Are Reclaiming Matters of the Heart. New York: Routledge.

Ginwright, Shawn A. 2009. Black Youth Rising: Activism and Radical Healing in Urban America. New York: Teachers College Press.

Padamsee, Yashna. 2011. “YASHNA: Communities of Care – Organizing Upgrade.” Retrieved October 14, 2016 (http://www.organizingupgrade.com/index.php/component/k2/item/88-yashna-communities-of-care).

Re-sources

Re-Imagining Education

Empowering educators to take a deeper look at the stories told in our schools and to re-imagine them in transformative and

nurturing learning spaces.

Learning Opportunities

Classes, workshops, and lectures that help to empower people to re-imagine who they are and their place in the world.

Get Involved

Help the Chicago Wisdom Project realize its mission to re-imagine education through holistic programming that transforms individual, community and world through creative expression.