“Gilgamesh, Where Are You Hurrying To?”:

Coronavirus and Humanity’s Search for Immortality

By Theodore Richards

“Gilgamesh, where are you hurrying to? You will never find that life for which you are looking. When the gods created man they allotted to him death, but life they retained in their own keeping. As for you, Gilgamesh, fill your belly with good things; day and night, night and day, dance and be merry, feast and rejoice. Let your clothes be fresh, bathe yourself in water, cherish the little child that holds your hand, and make your wife happy in your embrace; for this too is the lot of man.”

The Epic of Gilgamesh

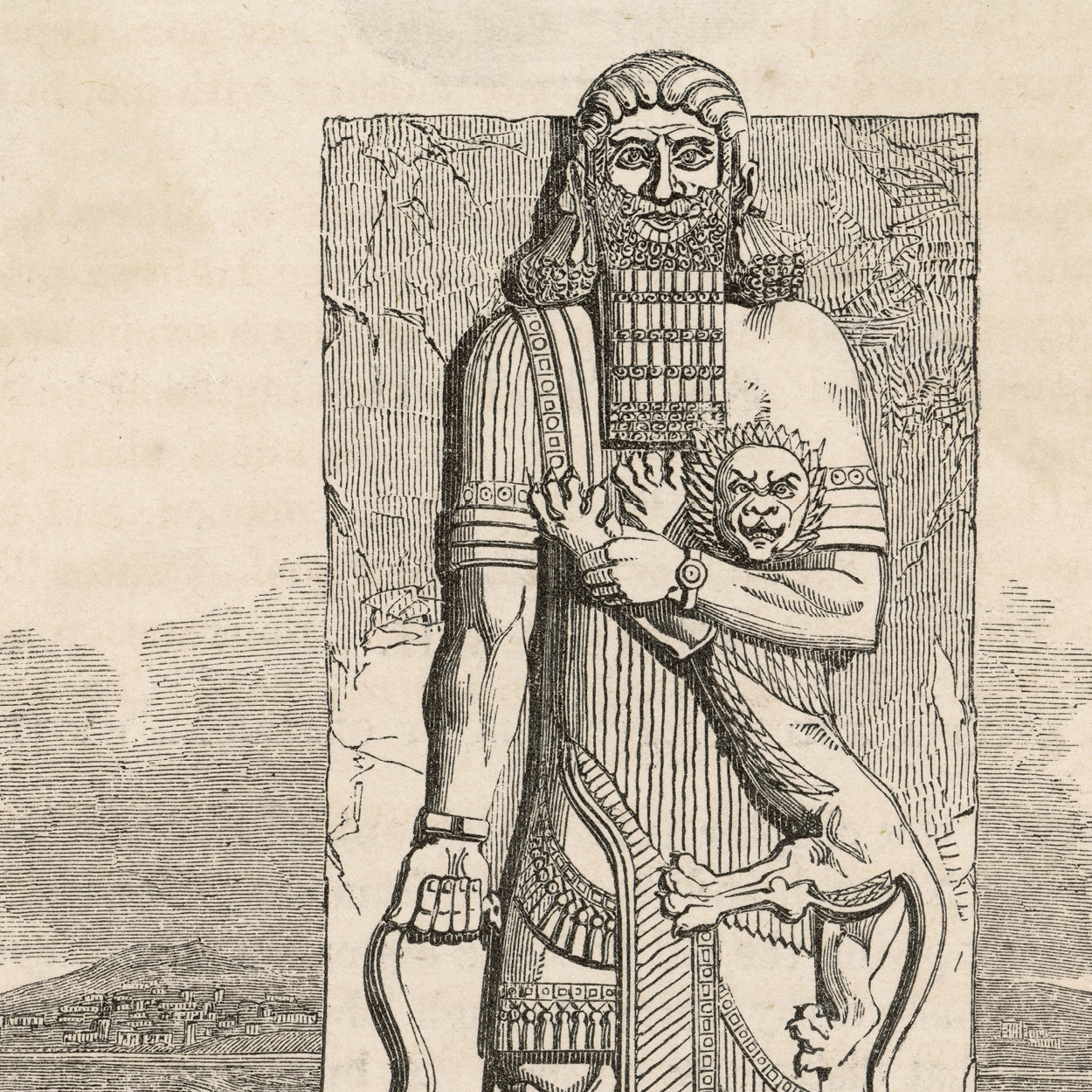

Among the surprising joys of the pandemic has been reading, with my six- and four-year-old daughters, a children’s version of The Epic of Gilgamesh. Perhaps four-thousand years old, the Mesopotamian epic is among the oldest surviving religious texts. And yet it remains remarkably relevant.

Gilgamesh is a king, a tyrant even, a builder of a great wall around his city, Uruk. He is part man and part god, which makes him at once strong and, perhaps surprisingly, weak. For he cannot recognize the value of human connection, of friendship. He only sees power and seeks to build walls rather than relationships. So many thousands of years later, we know of such men, and still contemplate the wisdom of building walls.

In response to this tyranny, the gods send Enkidu. He is also part man, but his other half is animal, wild. This wild man becomes Gilgamesh’s greatest rival and, ultimately, friend. He teaches Gilgamesh the joys and sorrows of human friendship.

But as he helps Gilgamesh become more human, Enkidu enters into the world of human civilization. He loses some of his wildness.

Human civilization is still, even now, brand new. It is an experiment, really, that may or may not succeed. For most of human history, we were more Enkidu than Gilgamesh. The rise of large-scale agriculture, urbanization, and empires – the civilizations of ancient Mesopotamia were among the first – radically altered human experience. We began to ask new questions. Immersed in the world of the forest, Enkidu would have seen that the animals, plants, and clan were enduring, and through them he would find connection and meaning. But Gilgamesh seeks after a different kind of permanence. He wants to be remembered for his wall and his empire. And ultimately, he asks, what is the fate of my own soul?

Together, Gilgamesh and Enkidu reject the goddess Ishtar and kill her bull. This rejection – of nature, of wildness, and of the goddess – leads us down the path of civilization, seeking to become more like the gods. In killing the goddess, in entering into this urbanized, imperial world, Gilgamesh and Enkidu are entering into a new kind of human consciousness. It is the world of patriarchy, and of alienation from the natural world.

In addition to the philosophical and spiritual dilemmas that come with it, there are also ecological and medical costs. Ishtar’s revenge is to send a plague to kill Enkidu. This makes sense; for the people who wrote this story, like all people living in large civilizations, would have known disease. Enkidu is killed for becoming what we may call “civilized” – it would be more accurate to call it “sterilized” – just as so many of us have been killed by the animal-borne diseases brought first by the agricultural revolution, and later by the industrial revolution (cancer, heart disease, obesity).

Today, we enter into the third phase of the diseases of civilization. AIDS, Ebola, SARS, and Coronavirus are diseases caused by the continued destruction of wild spaces.

Although Gilgamesh has learned something from his friendship with Enkidu, his response to Enkidu’s death shows that he is still a man struggling at the edge of the divine and human worlds. He goes on a final quest to find immortality. He fails, ultimately, and learns that he must honor his friend’s memory by being more human. But this quest remains our quest. We still seem to want to be like gods, intent on forgetting what it means to be human.

He only sees power and seeks to build walls rather than relationships. So many thousands of years later, we know of such men, and still contemplate the wisdom of building walls.

It turns out that humanity has been grappling with the same questions, the same struggle, since the earliest civilizations. The coronavirus pandemic can be understood as part of our continued rejection of our natural, human nature, of our encroachment on the wild. We have deluded ourselves into thinking we are gods – separate from the wild and our own wildness. This separation is the actual cause, and this notion that we can control things – to be gods – is the very source of our paving over of this world. It is the source of the ecological destruction, of the biological and cultural monocultures that have rendered us so vulnerable. This is what empire does: it turns cultural diversity into globalization, diverse ecologies into monocultures.

Four-thousand years later, we are still building walls, still building empires, still rejecting the goddess – and we are still rejecting and repressing the wild person inside ourselves. Our walls are both literal and figurative. We live, today, in lonely screen-worlds of individualized consumerism, each of us is a little Uruk unto ourselves.

We are also little Gilgameshes: each of us seeking immortality; each of us always on some kind of quest, looking for something else. If nothing else, the restrictions of the global pandemic are teaching us to be still. Gilgamesh, where are you hurrying to? We might have asked this of our entire species, up until a few weeks ago.

But we are not gods – we are merely animals who have learned to care for each other, like Enkidu. And like Gilgamesh, we must learn in these dark days to contemplate life and death, friendship and love.

Re-sources

Re-Imagining Education

Empowering educators to take a deeper look at the stories told in our schools and to re-imagine them in transformative and

nurturing learning spaces.

Learning Opportunities

Classes, workshops, and lectures that help to empower people to re-imagine who they are and their place in the world.

Get Involved

Help the Chicago Wisdom Project realize its mission to re-imagine education through holistic programming that transforms individual, community and world through creative expression.