Innocent Until Proven Black:

A Eulogy for Black Males…

But, Can We Live?

By Derrick Brooms

opening statement…

not a rappers delight

just trying to get my line tight

sharpening my forethought

meditating to get my mind right

willing to fast for freedom

brothers sitting on time

and I’m wishing my writing could free them

wishing the lighting could see them/ more

hoping my thoughts become before

we be claiming sets but

there be no return through that door

prelude the beginning

suffering mass incarcerations

but some claiming we winning

writing for half glasses

writing for love of the masses

we be scribbling freedom on pages

but can’t pass classes

still divorcing self of who I used to be

feeling the sun, letting the energy breed new to me

trying to have my heaven here on earth

repeating names of ancestors

cause this concrete hurt

banging on buckets

we still on the run

we still breaking north

like it was written in the drums

poetry for penitentiaries

suffering of centuries

they Trayonning our kids

we need sojourner truth ministries

the breakaways ain’t to baskets

we on riverbanks and in attics

writing theses that read like illmatic

my sketches still be post-traumatic

A Question of Architecture:

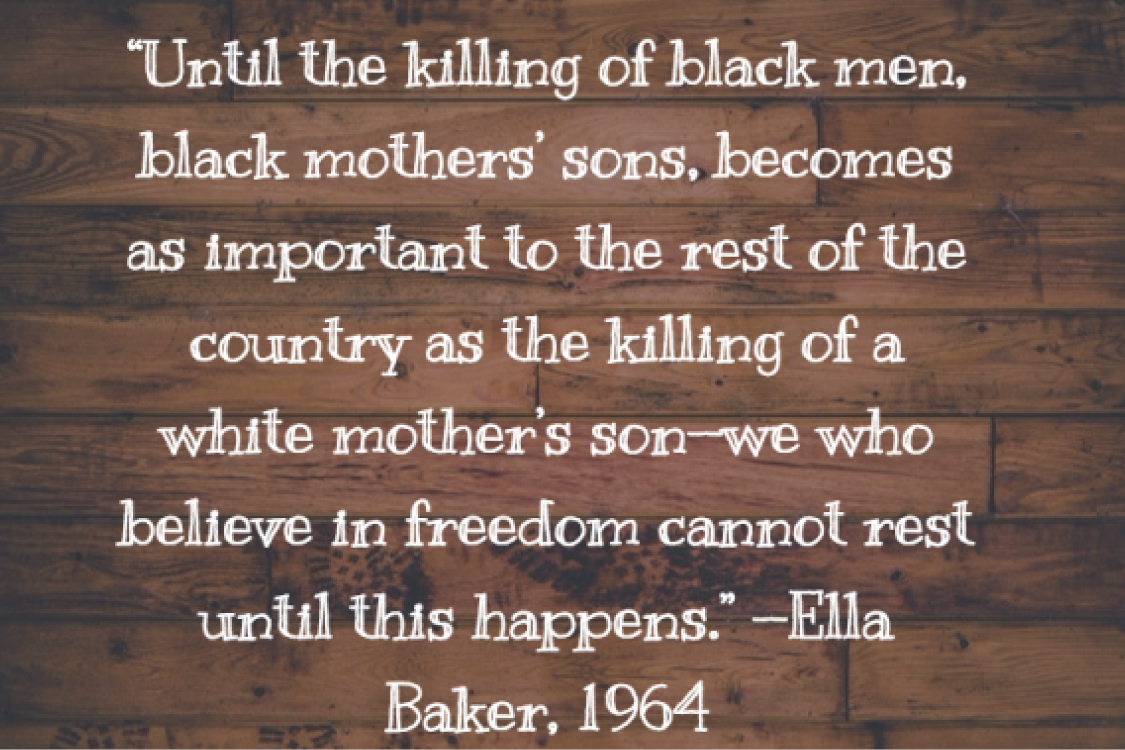

We are, in short, but two generations removed from the height of the Black freedom movement, a time period during the mid twentieth century in which U.S. society was on trial over whether Blacks – and other People of Color – had the same rights and freedoms as did whites. This is a criminally trivial dispute, worthy only from the standpoint of the dark holes and experiments that colonized North America and strangled the land from indigenous peoples. And, somehow, in uncanny fashion, these debates over the value of lives continue today. During the interim, the war on drugs and the war crime ravaged Black communities and left skeletal frames where families once resided. Both wars helped to drive and fuel mass incarceration, seemingly unleashed as part of a three-point program – miseducate, invalidate, and mass incarcerate – which has reigned terror on these same communities and families like Black Death.

Driving while Black.

Walking while Black.

Breathing while Black.

Stop and frisk.

Extrajudicial killings of Black people by police, para-police, and individual vigilantes; yet, these killings in public are no new venture. Our lives remain at risk. We have been at risk since we were plundered, bartered, betrayed, enslaved, sharecropped and chain-ganged, Jim Crowed, Samboed, assassinated in media projections, ghettoed in urban concentration zones, plea bargained and herded into prisons, killed in the streets.

The persecution of the Black male in the United States seems like a capital venture. Surely, Black males engage in behaviors that threaten their lives and impede their own progress; and, routinely, these actions and behaviors seem to receive disproportionate levels of media attention. However, these projections inform the crux of the narrative: Black males are dangerous, they are threats and prone to criminal activities.

Primarily, though, as reams of data continue to reveal, most personal crime is perpetuated against same-race peers. But there still remains the persecution. And the narrative. Contorted by controlling images, crunched by other people’s fantasies, dislodged by disposition and dislocation, all working to imprison us into dark matter. And the ways in which Black males are violated. The deciphering from the narrative is so thorough that the violence perpetuated against them can be interpreted as their own doing.

Still, the violence levied against them throughout history has not simply targeted Black men as a racialized-gendered group, but rather has taken aim at Black humanity. The violence propagated against Black males and the imagery used to misinform perspectives both are tributes to this. The legions of incidents propagated against Black males continue to mount. We find ourselves at a critical historical juncture within our short span of the 21st century, where labels that create images of Black pathology again accost us. The recent headlines that surrounded the Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, and Freddie Gray cases and the winds of violence against Black males within the confines of the United States are a testament to this.

We are made to fit descriptions that have been designed to contain us.

Too many Black males are innocent until proven Black. Too many Black males are concerned that they may be next in line for being victimized by violence – physical, emotional, mental, or spiritual. Constrained by controlling images that criminalize them based on their existence and overly punitive policies and regulations that are more invested in destroying Black minds and bodies than establishing justice. But it’s just us: driving, walking, shopping, playing, and breathing while Black… our humanity under constant attack. We are corner boys in an unremitting struggle.

Roll Calls From The Streets:

February 26, 2012: 17-year-old Trayvon Martin was murdered in Sanford, Florida by George Zimmerman. As details regarding Martin’s murder were revealed, a national public outcry ensued. Martin was villainized in the media; his race-gender identity as Black male immediately posited him as a likely suspect which, along with the hoody that he wore that night, led to Zimmerman’s profiling of Martin as a “suspicious character” that seemed to be up to “no good.”

In response to Martin’s murder, thousands of people voiced concerns for his profiling, they asserted challenges of current laws (such as “stand your ground”), and many protested. In an act of solidarity, people from all walks of life, including professional sports athletes, state legislatures, professors, and many community activists donned hoodies to stand in solidarity with Martin and called for a full investigation and Zimmerman’s arrest. Just over a year later, in July 2013, a jury acquitted Zimmerman of all charges.

The culmination of Martin’s murder and Zimmerman’s acquittal revealed the “problems” of Black male identity in the United States that noted scholar W.E.B. DuBois spoke of at the turn of the 20th century. The “problem” exacts that young Black males need to be policed and, therefore, are openly subject to racial profiling, stereotyping, and various forms of police malfeasance. The problem that haunts many Black male youth is, quite simply, the skin that they’re in. Thus, racialized identities become cause and concern for how Black males are engaged in society and how they’re treated. The “problem” is exacerbated by the legacies of racism and discrimination levied against Black males – both historically and within a contemporary frame.

The true tragedy of Martin’s case, despite the verdict and the laws that make such verdicts possible, is that his murder adds to the legions of racial violence against Black males in U. S. society. Some of the recent and more publicized incidences include the following (this is NOT intended to be an exhaustive list):

April 12, 2015: Freddie Gray died in police custody while being transported in a police van in Baltimore, MD. Nearly 80 percent of his spine was severed during the transport. Gray’s death ignited responses from local citizens and supporters, as the city erupted in protests and political action.

November 22, 2014: 12-year-old Tamir Rice was shot by police gunfire while at a park in Cleveland, OH.

November 20, 2014: Akai Gurley was shot and killed by police gunfire in Brooklyn, NYC. Police were patrolling stairwells in a housing unit and the shooting was declared an accidental discharge when a bullet ricocheted off the wall and struck Gurley in the chest.

October 20, 2014: Laquan McDonald was shot and killed by police gunfire in Chicago, IL. After not responding to a series of police orders, McDonald, shown in dashcam video footage moving away from police, was shot 16 times in 13 seconds by a Chicago Police Officer.

August 9, 2014: Michael Brown was shot and killed in Ferguson, MO. The shooting prompted a wave of protests in Ferguson and across other cities for weeks. In March 2015, the U.S. Justice Department declared that Ferguson had engaged in constitutional violations and called for overhauling its criminal justice system.

July 17, 2014: Eric Garner died in Staten Island, New York City after being placed in a chokehold by an officer from the New York City Police Department. 11 pleas for breath later, ensconced in our collective memory, Garner’s repeated statements of “I can’t breathe” is difficult to phantom and even more troubling to hear/witness through video recordings. Garner’s final words – “I can’t breathe” – became a rallying cry in calls to remember his fatal struggle and was used to link his fate to the lives of other Blacks in the U.S.

October 8, 2013: Jack Lamar Roberson was shot and killed by police in Georgia. According to his family, an emergency call was made for help as Roberson was experiencing an adverse reaction to medication he took for his diabetes. Police claimed that he was armed and they had no choice but to shoot him.

September 16, 2013: Johnathan Ferrell was shot and killed by police in Charlotte, NC. Ferrell, who struggled after being involved in a car incident and knocked on a door in an attempt for help, was reported as attempting to “break and enter” into a home. Police reported that when they arrived at the scene, a man matching the description ran toward them. In response, Ferrell was fired upon several times.

July 27, 2013: Roy Middleton was shot twice by police in Pensacola, FL. A neighbor called police and reported Middleton as a potential car thief as he searched through his own car in his own driveway. Upon arrival, the police reported that he refused to obey commands and, at one point, lunged upon him. In response, they shot at him 15 times.

November 23, 2012: Jordan Davis was murdered in Jacksonville, FL. Davis and another youth were fired upon while sitting in a car at a gas station after Michael Dunn confronted them because of the volume of their music. Dunn claimed that he was threatened and that a shotgun was pointed at him; he responded by firing eight shots from his handgun where three struck and killed Davis. Police investigated and found no guns in Davis’s car.

Nov. 11, 2012: Leon Ford Jr. was pulled over by police in Pittsburgh, PA. The main tenets in this case center on the justification for stopping Ford and what ensued during his interaction with police. In the aftermath of the contentious interaction, he was shot four times and paralyzed from the waste down.

January 1, 2009: Oscar Grant III was shot and killed by a BART police officer in Oakland, CA. After responding to reports of a fight on a local train, Grant and several others were detained at the Fruitvale BART Station. He was accused of resisting arrest and the officer, Johannes Mehserle, shot a handcuffed and faced-down Grant in the back.

Within our current time, over the past few years, we have seen an explosion of activism in large part as a response to the recent and ongoing killing of Blacks – including the short list highlighted in the stories above. And, these events, incidents, and killings must be viewed within the purview of Barack Obama’s presidency. The response: the #BlackLivesMatter campaign that was birthed in a moment and has served as a national movement and call to action. #BlackLivesMatter was created by Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi, three Black women, in response to the anti-Black racism that permeates throughout U.S. society.

Redlining.

Residential segregation.

Dilapidated housing.

Entrenched systemic and institutional racism.

Separate and unequal.

Disparate economic opportunities.

Educational opportunity gaps.

Minimum wage versus living wage.

Snail’s pace reform.

1.5 million Black men missing.

Disproportionate incarceration.

If Not In The Streets Then In The Courts:

Too many Black men are guilty until proven innocent. Pleas are offered as bargains. Prisons institutionalize a new form of Black death. Where Black life is choked out and too many Black males are dying to live. Discipline and punish. Like the depravity of Black lives and humanity.

The U.S. criminal justice system is misnamed. As others have noted, and as has been even more apparent in our recent time, the system is set up to enforce laws. Too many U.S. courts stamp with approval that which occurs on streets: Black bodies left bloodied and murdered; yes, Black lives matter… quite differently than others. Too many injustices inherent in the killing and imprisoning of Black life.

“We have more work to do when more young black men languish in prison than attend colleges and universities across America.” – then-Senator Barack Obama, 2007.

The Mass Incarceration of Black Males: The New Jim Crow

We who have suffered. For most, freedom is a right; for us, freedom is the price our bodies pay for national calamities. We have been serving and in the service since the Mayflower, and we have been on trial ever since. Convict leased. Black codes ensured that we provided labor while simultaneously criminalizing Blackness. Prison, the new virus, has commodified our futures.

Stuck in a carceral state like exiles. We are Angola (Alcatraz of the South), Parchman Farm, and debtor’s prisoners. Private corporations lobby and fund political campaigns for the capitalized opportunity to confine our bodies. The new pipelines. Colored by disproportional Blackness, our targeting started at Jamestown and reveals a multi-generational racial imbalance in how laws are enforced.

Incarceration has run its own independent course; defying correlations to crime and safety. Slavery is still legal as a form of punishment. Neighborhoods are stopped and frisked – by tangles of deprivation. The mundanity of imprisonment as both policy and response has created realities that allow surveilling and paroling our past, present, and future a new norm, such that our dislocations seem imminent. From Cabrini Green to Henry Horners, from Altgeld Gardens to Robert Taylor Homes, prisonizing non-prison spaces, death sentences without trials.

The spatial containment of Blacks is nothing new. You have to confine the spaces available to them and then further restrict the space so that it engulfs the body. That is, “prison” and “incarceration” can be architected into the landscape. Whole communities can be (re)designed to immobilize the populace. We who have been surveilled, restricted, and sanctioned. How many lives and families are imprisoned in concentration zones?

The burden has been laid bare. The mighty stream dried as quickly as the ink persecutes us into another cell, arrest, profile, stereotype, and random search.

Imprisonment has been refashioned: out of sight, out of mind; keep the trouble away; they who deserve no freedom. No need to rehabilitate. Spatial disempowerment. All too often, Blacks are placed outside of the law, a law that has been pursued for over two centuries. First, to be counted as full citizens. Then, to be treated as full humans. The post-traumatic is the most traumatic. From Dred Scott to Bloody Sunday. Feet wearied. Today’s injustices have been centuries in the making. Mass incarceration makes possible for human bodies to flow and be trafficked between public and private entities like cargo, reminiscent of past endeavors.

The innocence of this country was plundered along with indigenous tears that trailed the indignations and misery consigned to them. The innocence was forfeited like the lifeless treaties that created reservations, birthed denial and destitution on plantations and dust tracks, buried hopes in interment camps, herded deferred dreams into urban holding cells, the future generations of outsiders within. The contemporary form of Black body snatchers leave us mass incarcerated.

Too often the actions of a single officer are set ablaze in our reactions – such as in Trayvon Martin and Eric Garner’s cases – and less attention is given to the systems that allow for a shoot first mentality. The question is not whether George Zimmerman was wrong in following and pursuing Trayvon Martin. The question is not whether the chokehold used by Officer Daniel Pantaeleo that subdued Eric Garner was legal. The question is not whether we have more Black males in prison today than those enrolled in college. What happens when the cameras and microphones are gone? What is to be said about life, and life chances, in communities that are too often used to drive-by reports? What does it mean to live in a society where too often a particular segment of the population, Black males as argued in this essay, is presumed guilty first? If we are presumed guilty, the question is not what of our innocence but rather what is to be the punishment.

The carceral state so malignant even our development is arrested.

Our incarceration and lack of opportunities are the upswell.

Our freedoms get hung like juries.

When do we address the architecture?

Re-sources

Re-Imagining Education

Empowering educators to take a deeper look at the stories told in our schools and to re-imagine them in transformative and

nurturing learning spaces.

Learning Opportunities

Classes, workshops, and lectures that help to empower people to re-imagine who they are and their place in the world.

Get Involved

Help the Chicago Wisdom Project realize its mission to re-imagine education through holistic programming that transforms individual, community and world through creative expression.